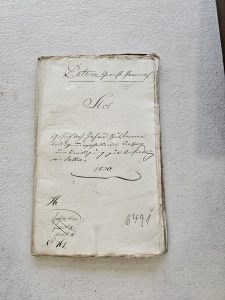

II.1.10 A resident permit

Johann Hutsteiner requested a resident permit in Solla 1830. Such requests about residence permits we ccan find several time for our fellow ancestors, too

In the 19th century it was still common for a farmer’s family – the villagers all subsisted on their own crops, no matter how meager it may have been – to have many children. On the one hand, this was the pride of the father, on the other hand, many children died in the first two years. However, when they were of marriageable age, the problems really began: girls had the chance to be married; The prerequisite for this was almost always a certain “souvenir” that had to correspond roughly to the groom’s possessions, or they eked out an existence somewhere as a maid for the rest of their lives. This matter was almost even more hopeless for a “young man”. One of the children got the parental property, but given the small size of the property, it was almost never shared; everyone else had to watch where they stayed. The second or later sons of a largely self-sufficient family had usually learned their father’s trade if he had specialized in, for example, a butcher, bricklayer, carpenter or cooperator; the job only secured a living if there was sufficient demand, so that the son could often only settle in places where this job was not yet offered. Factory work in the city did not yet exist, so life was often predetermined as a servant or day labourer for another farmer, unless you could marry somewhere. In their own place of residence, however, everyone knew about the financial needs/bottlenecks of the others. So marrying into neighbouring towns or even further away often seemed a feasible way out.

The state was slowly becoming aware of some of its obligations towards its subjects and had introduced rules that concerned the livelihood of the poorest. Every person, as long as they were unmarried, had a “right of home” in the place where they were born. This included support from this community in case of poverty with housing and food. With the marriage, this obligation was transferred to the community in which the marriage took place, which is why all communities wanted to be informed before the marriage and taking up residence there as to whether it was to be expected that the need for care for the poor would occur at a later date. This was regulated in the law with the catchphrase: Is the food supply for a family secured by the groom? Otherwise, a marriage and thus a settlement in this community could be prevented by non-permission. Since permission to marry was sometimes refused, this resulted in many illegitimate, i.e. premarital, children of the loving couples.

Before the church marriage, the groom applied to the community and its care for the poor, which was then forwarded to the competent regional court. This was discussed with the mayor, who was mostly illiterate in writing and form, and whose clerk then wrote down the result by hand.

Necessary requirements for marriage:

- Birth certificate for bridegroom and bride – since there were no registry offices, the parish where the baptism had taken place was allowed to confirm the name of the baptized child, his date of birth and baptism, and the names of the parents from the baptismal register.

- A certificate of good conduct had to be produced for both of them, which was issued by the parish leader or pastor of the previous place of residence, in which illegitimate children and paternities also had to be named.

- A vaccination certificate against smallpox was required.

- Both had to submit a certificate of attendance at the weekday and holiday schools. The latter was the same as the first, but allowed commercial work on weekdays and required visits only on Sunday afternoons. Grades were less important, much more the fulfillment of compulsory schooling, which many parents/children avoided until 1920 because they had to contribute to the livelihood through work; (see today the lives of children in developing countries).

- Finally, the groom had to prove that he had fulfilled his duty with a “military discharge certificate”. I often found the following note in it: “not drafted from the list of conscripts of the year because of a high ticket number” (rarely because of unfitness for service), which means that not all conscripts have also done military service. It also contained the remarkable sentence: “…the same man…was expressly made aware of the ban on entering foreign military service without special, highest permission.”

- And then the minutes included a detailed statement by the groom on how he wanted to secure the food supply for himself and his family for the coming decades. Even the person who took over the farm had to prove ownership, i.e. the takeover of the farm, by means of a notarial deed before marriage (the previous farmer “going out”) so that the poor relief organization could give their consent.

Such residency and marriage files of the regional courts exist from around 1812 to 1876, after which civil status was the responsibility of the registry offices.